What were the Witch Trials?

Where did the hysteria surrounding witches come from in early modern Europe and North America? Learn more about this fascinating history in our newest post to the Ask a Historian series!

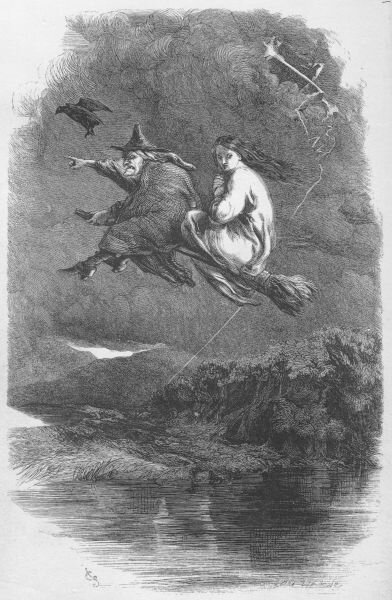

Myths about humans with access to magic or other supernatural powers have existed for thousands of years. These ideas have been present since the ancient world—priests were thought to be able to wield magic in ancient Egypt—and even remain with us today through popular fantasy novels and films. In early modern Europe, accusations of witchcraft—most often but not exclusively aimed at older women—reached a crescendo between the mid-1500s and the mid-1600s. During this time, thousands if not tens of thousands of people were executed for the crime of being witches.

So why did this happen? To start to answer this question, it is important to consider the wider historical context. These years between 1550 and 1650 coincided with a major period of upheaval in western Europe. Specifically, these were the years of the Reformation and the Counter-Reformation, when Protestant sects broke away from the Catholic Church due to a variety of theological and political disagreements. Across Europe, countries, regions, principalities, and towns were now at odds with themselves and their neighbors over which religious beliefs should be followed and which should be condemned as heresy. This rupture also overturned an order that had underpinned Europe for over a thousand years. Namely, whereas the Catholic Church had once been a unifying force across western Europe (with the head of the Catholic Church, the pope, wielding considerable influence), now this commonality was suddenly gone. In its wake, political, social, and cultural disruptions reverberated across Europe throughout the century.

These witch hunts coincided with the new religious conflict between Catholicism and Protestantism in western Europe and perhaps this wider sense of destabilization created a sense of fear and also a power vacuum in which these trials could take place. That said, it is important to point out that there does not seem to be a correlation between one denomination and witch hunts: some Catholic and Protestant states saw wide-scale witch hunts, while other Catholic and Protestant states saw relatively few.

For instance, one of the largest witch trials took place from 1581 to 1593 in Trier, in what is now Germany. At the time, Trier was a Catholic diocese in central Europe, and this witch hunt was encouraged directly by the leader of the Catholic Church in Trier, Archbishop Johann von Schönenberg. This trial resulted in perhaps the deaths of some 1000 people in and around the city of Trier. No one was safe from fatal accusations of witchcraft: men, women, and children (as well as both commoners and nobles) were victims in this witch hunt.

Witch hunts also took place in Protestant areas. Britain saw large witch hunts. For instance, in 1612, a series of witches were put on trial in and around Lancashire. Known as the Lancashire Witch Trials, a dozen people (mostly from two rival families) were charged with witchcraft, only one of whom was found innocent. However, Britain passed the Witchcraft Act in 1735, which made it illegal to accuse anyone of having magical abilities. This legislation effectively ended witch hunts in the UK.

These witch hunts also made it across the Atlantic to the European colonies in North America. In the United States, the most famous example comes from Salem, Massachusetts. The Salem Witch Trials lasted from 1692 to 1693, halfway between the establishment of the first permanent English colony (Jamestown, 1607) and the Declaration of Independence (1776). These trials took place in the Puritan colony of Massachusetts, which was known for demanding that its colonists adhere to a strict religious orthodoxy. Over twenty people were executed or perished in jail during the trials, and around 200 people in total were accused of witchcraft. The horrors and the arbitrary nature of who was accused, murdered, and allowed to walk free remain with us today as a chilling testament to the devastating consequences of groupthink and vigilantism. Throughout the following centuries, family members and locals have been working to clear the names of the people accused of witchcraft and executed for the crime of witchcraft during the Salem Witch Trials.

Tens of thousands if not hundreds of thousands of people were accused during these trials, and also many thousands of people died. It is important, then, to ask about the underlying causes of these witch trails. Barring the possibility that these individuals did indeed have magical powers and were being charged for having supernatural powers that they did indeed possess (unlikely), what was the impetus behind these witch hunts?

For some historians, these witch hunts were conducted in response to local problems or disasters. In this time, there were numerous instances of crop failures or famines. Indeed, the height of the witch hunts in Europe coincided with a relatively cold period, known as the Little Ice Age. Perhaps the witch hunts stemmed from looking for someone to assign blame to during difficult times. Indeed, we can trace some witch trials directly to particular historical events. For instance, when James VI of Scotland and Princess Anne of Denmark faced severe storms during their voyage from continental Europe to Britain, women in both Britain and Denmark were accused of using witchcraft to cause the storms.

Another group of historians has argued that misogyny was a cause of the witch hunts. Around 80% of victims were women, mostly older women. Older women typically had fewer protections in Europe and North America at this time, so they were relatively weak members of society with very few protections. Indeed, in the case of Europe, it might have been the case that there were more unattached, older women present that had been before. Following the closures of convents in the Protestant Reformation, women who had joined religious orders needed to return home, where as unmarried, childless older women, they didn’t clearly fit into social arrangements of the time. Moreover, women who in an earlier decade would have joined a religious order now had nowhere to go.

Other historians have argued that perhaps the issue was the lack of central authority within states in early modern Europe. Many witch trials were conducted outside of the usual legal protocols, meaning that officials could not step in to conduct the trials, and presumably end them. Instead, local leaders or local frenzies took the situation out of hand. Perhaps the fact that witch trials died out by the 1700s—when European countries were consolidating and centralizing their power—indicates that this lack of state power was an avenue that permitted the witch trials to take place.

While research remains ongoing into the causes of these witch hunts, the witch hunts themselves remain important for the study of the past. In some ways, witch hunts helped lessen the grip of religions over specific communities. In the aftermath of these witch hunts, members of the faithful asked how religious beliefs had led to such violent ends. Furthermore, these trials provide an important lens into how historians study the past to learn about gender roles and power imbalances.

Research your Own Questions about the Past

Join the Circa Project