The Time When 10 Days Disappeared from the Calendar

Countries across Europe gradually changed their calendars starting in the 1500s. Why did they need to change the dating system? And why did everyone have to skip forward a week and a half? Read this post about the history of the modern calendar to learn more!

By the mid-1500s, there was a problem with the calendar being used in many places across Europe. Although the calendar was designed to correspond with the movement of the Earth around the Sun, days were beginning to draft. Days that used to mark equinoxes and solstices were slowly slipping away, meaning that the calendar system was no longer aligned with its solar markers.

The reason for calendar reform in early modern Europe stemmed from a slight miscalculation with the previous calendar. This calendar was actually quite old, even by standards of the 1500s. The calendar in use at the time had been first created under the rule of Julius Caesar (hence the name, the Julian Calendar) and had taken effect in 45 CE.

In many ways, even though the Julian Calendar is now over 2000 years old, it strong resembles our calendar system today. There were 12 months, with names and day lengths that are more or less identifiable today: Ianuarius (31 days), Februarius (28 days; leap years: 29 days), Martius (31 days), Aprilis (30 days), Maius (31 days), Iunius (30 days), Quintilis (31 days), Sextilis (31 days), September (30 days), October (31 days), November (30 days), and December (31 days).

The Julian Calendar even had leap years every 4 years, which is also a familiar concept to us. However, it was with these leap years that the problem of the solar alignment of the calendar occurred. The Julian Calendar calculated the year as 365.25 days long, meaning that one leap year every four years would be needed to correct for any temporal drifting. However, this number was very slightly inaccurate: the length of a year is closer to 365.24217 days. This might seem like an insignificant decimal point: each year was only off by .00783 of a year. However, it did mean that every 128 years, the Julian Calendar system fell an addition full day behind the solar year.

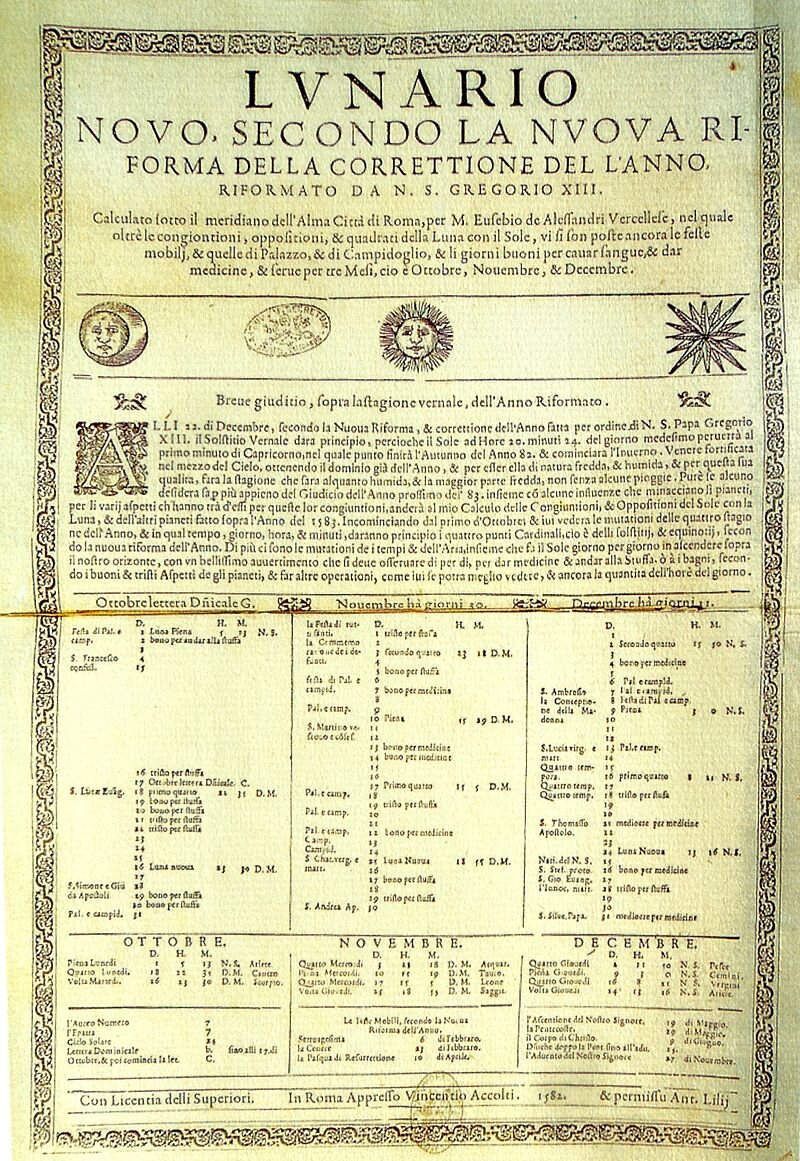

Over the centuries, these fractions of a day begin to add up, and by the end of the Middle Ages, this drift between the calendar and the solar year had become significant. In 1582, Pope Gregory XIII introduced changes to the calendar system to address what had now become a significant discrepancy between the calendar year and the solar year. In particular, this difference really mattered to Gregory and to the Catholic Church: the date of Easter is calculated based on the spring equinox. But because of this slipping of days, the date of the equinox was no longer where it was supposed to be on the calendar, meaning that the date for Easter was also askew.

The reform that Gregory introduced was to have a more accurate way of adding in leap days. The Gregorian Calendar still had leap years, but it used them slightly less frequently to avoid falling behind the solar year. Leap years would be added as follows:

years divisible by 4 would be leap years (just like before)

years divisible by 4 and 100 would not be leap years

years divisible by 400 would be leap years

Under this system, 1904, for instance, would still be a leap year. 1900, however, would not, since it is also divisible by 100. The reason why most of us living today do not know this rule is that the most recent year divisible by 100 (namely the year 2000) was ALSO a year divisible by 400, so it remained a leap year. This quirk of skipping years divisible by 100 will come back into effect in 2100. Ultimately, this change made the Gregorian year more accurate: it was 365.2425 days long, as opposed to the Julian calendar’s 365.25 days.

Most Catholic countries in Europe, which recognized the religious authority of the pope, adopted the calendar reform right away. This necessitated the skipping of 10 days to realign the calendar with the solar year. Protestant countries in Europe also adopted the calendar, although at a later date. The British Empire, for instance, only adopted the calendar nearly 200 years later, in 1752. Russia did not switch calendars until after the collapse of the Russian Empire in 1918, which is the reason for why Vladimir Lenin’s famous revolution, which took place on what we now call November 7, 1917, is known as the October Revolution, since according to the Julian Calendar (which Russia used at the time), it was still October.

The calendar system that we use today, then, is both very ancient but in other ways particularly modern. Some countries did not adopt it until the 20th century, and of course some countries and institutions continue to use their own calendar systems.